The Importance of Agrobiodiversity Conservation

Seed banks around the world are promoting agricultural biodiversity, helping farmers and plant breeders develop new varieties of crops for future generations.

If you’re an adventurous eater, you may know where to sample a Singaporean omelet or taste the best tikka masala. But even with so many culinary delights at your fingertips, you’re likely missing out on a lot of what nature offers up for dinner.

Take the humble potato. The average American eats about 117 pounds of potatoes every year—almost all of them some version of russets. Yet there are more than 4,000 types of potatoes native to Peru, where they were first cultivated 10,000 years ago. So why are we limiting ourselves to one or two varieties? The answer is complex.

Everything we eat, from apples and arugula to beef and butter, relies on a healthy system of agricultural production. Farmers harvest produce that feeds both people and the animals we rely on for food. That system, in turn, relies on biodiversity. But agricultural practices like monoculture farming, global tastes, urbanization and climate change have severely limited the genetic diversity of the crops we grow and the food we eat. At the same time, a surging global population is hungrier than ever.

The average American eats about 117 pounds of potatoes every year—almost all of them some version of russets. Yet there are nearly 4,000 types of potatoes native to Peru.

Promoting diversity

In hopes of preserving the world’s genetic heritage and reversing the loss of biodiversity, researchers are cataloging and carefully maintaining millions of agricultural species in seed banks around the world. From the remote permafrost of Norway to the American Midwest, these banks house samples of 7 million agricultural species. From Abelmoschus esculentus (okra) to Zea mays (corn), seed vaults contain all the genetic information necessary to build, or rebuild, our global food supply.

This critical endeavor requires major support, and an international independent organization called the Global Crop Diversity Trust (Crop Trust) provides just that. Founded in 2004, this brain trust of scientists and experts has worked closely with gene banks to provide equipment, supplies, and invaluable knowledge. The Crop Trust has helped rescue endangered agricultural species and multiplied samples of some varieties as needed, storing backup copies of them in the Svalbard Global Seed Vault on the Norwegian island of Spitsbergen, perhaps the most well-known of the world’s backup seed banks. The Crop Trust also oversees the 11 international seed banks of CGIAR, a global partnership of food-security organizations.

Despite its urgency, this work often goes unnoticed by the general public. With this in mind, the Crop Trust recently launched the Food Forever Initiative to educate consumers and the agricultural industry about the importance of diversity. And the Crop Trust is raising an $850 million endowment fund to maintain efforts to conserve the diversity of the most important food crops for humanity.

What’s driving the Crop Trust’s dedication to diversity? After all, most of us already have an incredible array of dietary choices. The problem is, in the decades to come, water supply, climate, and population density will all impact what’s on our dinner plates.

With more than 30 years in the field, Cary Fowler, one of the Crop Trust’s senior advisors and its former executive director, is probably the best person to explain why agricultural biodiversity matters so much. First, he emphasizes that the plants we cultivate for food for both humans and animals are part of the environment, both impacted by and impacting the natural world. “Any crop that fails to evolve—any crop that we fail to help adapt—will eventually perish and become extinct,” he says. In other words, we can’t assume that today’s blueberries and coffee beans will thrive in tomorrow’s climate. “That’s why I think of crop diversity as the most precious and important ‘natural’ resource on earth. It is the biological foundation of our food supply.”

“I think of crop diversity as the most precious and important ‘natural’ resource on earth. It is the biological foundation of our food supply.”

—Cary Fowler, Senior Advisor, Crop Trust

Tradition meets technology

Since the advent of agriculture, farmers have understood that not all crops are suited to all environments. With this in mind, farmers have long selected for the traits that thrive in their corner of the world. This practice of selection has allowed human beings to flourish for millennia.

With time and technology, the practice of genetic improvement has become more sophisticated. Today, agricultural researchers can pinpoint genes with precision to maximize plant hardiness and crop yields and minimize the need for pesticides and fertilizers. The diversity of our food crops is critical in preparing for the future, since each variety has unique strengths and advantages. In some cases, whole seeds are banked, but Fowler notes that genetic samples extracted from the seed are more reliable and robust. This material is then frozen and saved in banks for future use by farmers and researchers.

Fowler is quick to point out that this practice of gene selection is different from that of gene modification. “Both GMO and non-GMO varieties depend on conserving and using crop diversity,” he says, “including in traditional plant breeding programs.”

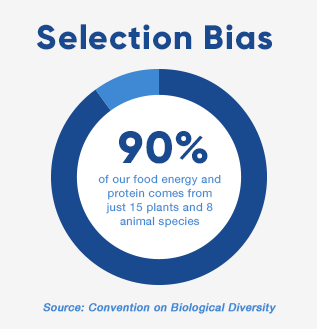

At the same time, global tastes have shifted, and more consumers are demanding the same crops worldwide. In fact, diet diversity around the world dropped by 68 percent between 1961 and 2009, and 90 percent of our food energy and protein now comes from just 15 plant and 8 animal species. Monocultures—massive plantings of the same crop variety—are commonly farmed to serve global demand. But since these crops are all vulnerable to the same diseases, whole fields can be wiped out at once when disaster strikes, leaving farmers with no crops at all.

Climate change presents further agricultural vulnerabilities, since crops that can be relied on today may not thrive or even survive as weather patterns shift. This is a particularly critical concern for the small farms that still feed much of the developing world.

These challenges are particularly stark against the backdrop of a surging global population. Today, according to the FAO, 821 million people throughout the world are malnourished, while world population continues to increase by about 83 million people per year. In the coming decades, researchers and farmers will have to work together to meet their needs—without overtaxing natural resources.

New solutions

The need for biodiversity in agriculture is clear. But averting a crisis will require a concerted, global effort to ensure the security of future agriculture. With this in mind, Food Forever is engaging in a public conversation to help consumers understand how agriculture impacts them. Since great conversations start over dinner, the organization is partnering with innovative chefs who prepare rare ingredients, highlighting the exciting flavors of lesser-known foods like algae and crickets—even for diners who might be reluctant to try them at first.

The Crop Trust isn’t alone in its efforts, of course. For millennia, farmers have saved seeds from bountiful crops to replant later. Today, a renewed interest in heirloom produce prompts growers around the world to seek out and nurture rare breeds. In Italy’s Umbria region, Isabella Dalla Ragione has founded the Archeologia Arborea Foundation. It’s the culmination of decades of work researching, discovering, and growing vanishing agricultural treasures.

Today, a renewed interest in heirloom produce prompts growers around the world to seek out and nurture rare breeds.

Across the world in Syria, plant conservationist Ali Shehadeh was doing the same work, carefully tending a bank of thousands of seed varieties, called the International Center for Agricultural Research in the Dry Areas, or ICARDA. His goal is to protect the unique genetic material of species that can survive in hotter climates. Syria’s civil war, however, forced the abandonment of the project, which is now housed in ICARDA gene banks in Lebanon and Morocco.

These efforts to preserve lesser-known varieties are small-scale versions of the seed bank work that Cary Fowler has devoted his career to. Each is a treasure chest of biodiversity, containing the tools needed to sustain agriculture in an uncertain future. As time goes on, the Crop Trust will do more than help various groups store seeds and genes. It will draw upon them as needed, sharing ideas and tools that support agriculture, and in turn, hungry people.

Preparing for the unknown

It’s hard to predict the future of our food. With the threat of bigger storms and higher temperatures due to climate change, farmers will need to have an arsenal of alternatives at the ready. Crops that have traditionally fed the world may not fare as well in a new climate, but with robust crop diversity collections to choose from, growers can adjust accordingly so that your coffee and muffins will always be there for you in the morning.

Additional Links

In Pursuit of Sustainable Agriculture

Building Resilient Food Systems

Combatting Food Insecurity through Sorghum